I’ve loved the idea of online multiplayer games for a long time. I think there are lots of really interesting ways shared, near-realtime apps can be used for remote gaming, in-person gaming, or more serious collaboration.

A friction point for me, personally, has always been Websockets. They are such a good solution compared to polling or other workarounds. There hasn’t been a serverless solution though – at least in AWS – so to use them, I’d need to deal with keeping a server running, patched, scaling, monitored, etc. And since this is not my day job, those aren’t chores I want in my hobby time.

In December 2018, AWS gave me a nice Christmas present: WebSocket API support for API Gateway. I filed it away on my todo list to play with at some point, and then 2020 happened. Suddenly, being able to do online collaboration of all kinds got a lot more important!

Update, March 2021: This post explores an end to end worked example of a browser-based multiplayer game. It uses a fairly simple game, so the game itself does not obscure how the architecture works. After some questions about this post, I have written a new one which looks at just how far you could take such a design. Please check out What are the limits of serverless for online gaming? if you’re interested.

The Game: Rock Paper Scissors Lizard Spock

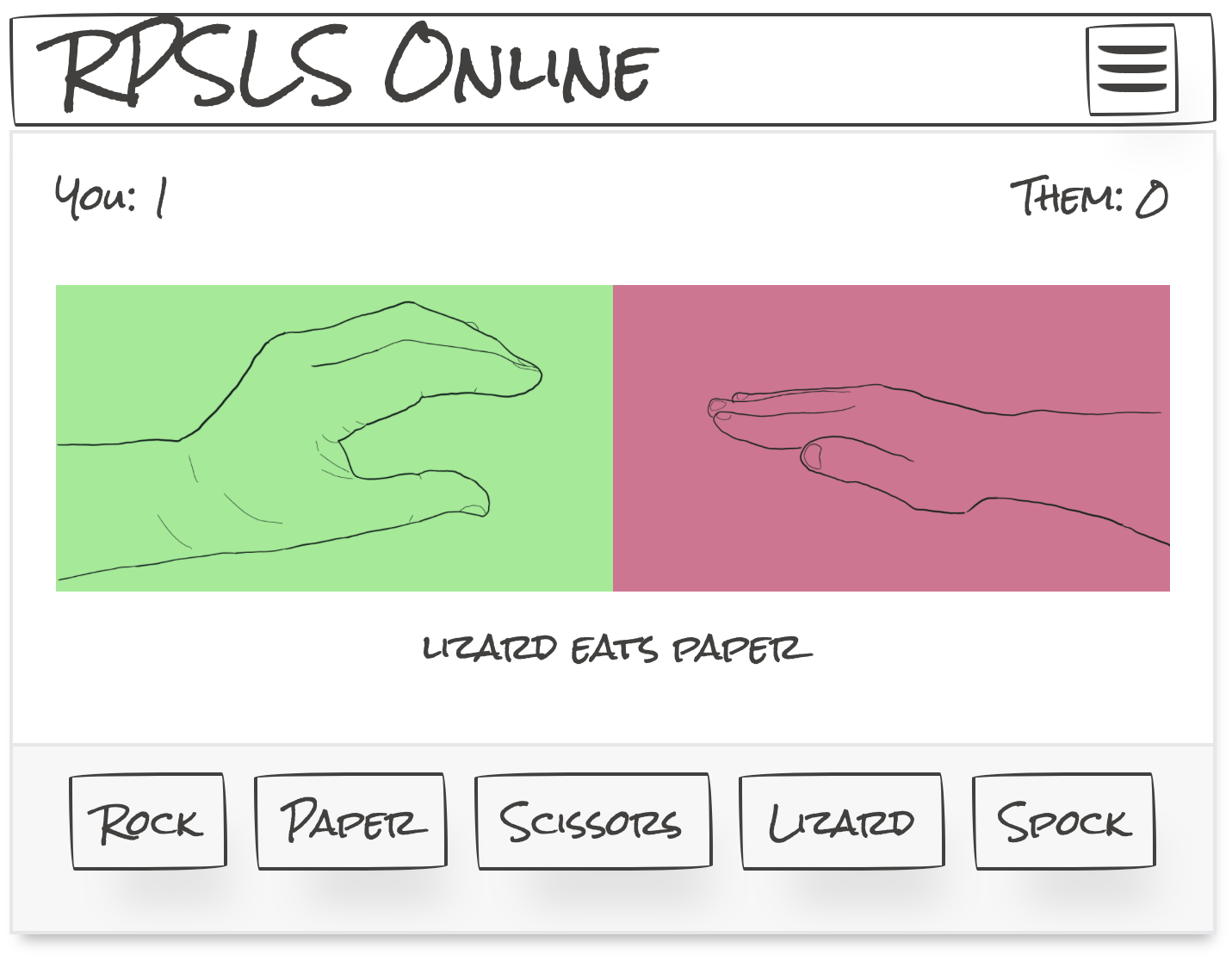

For this demo, I wanted to keep the game itself very simple – so the frontend and backend would be easier to understand without a lot of game logic getting in the way. But – not so simple that it would be completely boring. So, it’s rock paper scissors, but the 5 move variant invented by Sam Kass and popularized by Big Bang Theory.

It has all the normal rules, as well as:

- Rock crushes Lizard

- Lizard poisons Spock

- Spock smashes Scissors

- Scissors decapitates Lizard

- Lizard eats Paper

- Paper disproves Spock

- Spock sits on Rock

You can play the game described in this article right here:

Rock Paper Scissors Lizard Spock Online

Just copy the link and share with a friend (or grab a mobile device) and you can try it out.

It does store a random user identifier in localstorage, so if you want to play yourself in the same browser, one window will have to be on incognito mode or a different profile.

The Architecture

The full source is available in github at jbarratt/rpsls.

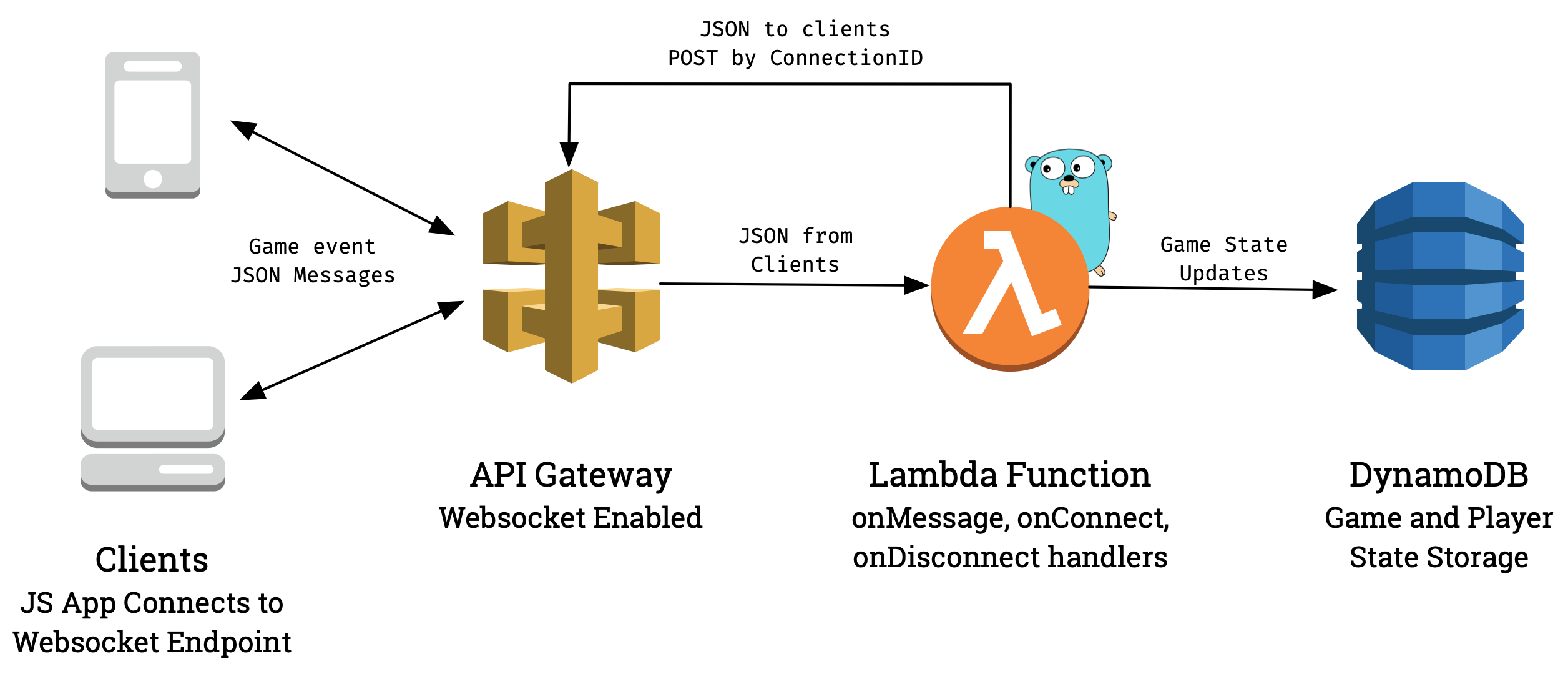

The architecture itself is fairly simple:

The API Gateway WebSockets implementation allows two methods of communicating with the clients, either replying to a message they sent, or POSTing to a special endpoint and including their connection ID. For this app, all game state changes are broadcasts, so for simplicity they all use the POST channel.

Clients run a javascript single page app, which uses websockets entirely to communicate to the backend.

It speaks a simple JSON protocol. (Relevant Go Types)

Clients to Backend

| Key | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

action |

string | What the user is doing (new, join, play) |

userId |

string | A unique identifier for the user, usually randomly generated |

gameId |

string | The ID of the game. Usually a 6 character string of letters and digits |

play |

string | When action is ‘play’, what move to make. (rock, paper, scissors, lizard, spock) |

round |

number | When action is ‘play’, what round is being played. |

Backend to Clients

| Key | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

round |

number | What round the backend is currently accepting plays on |

gameId |

string | The ID of the game. Usually a 6 character string of letters and digits |

yourScore |

number | The player’s score |

theirScore |

number | The opponent’s score |

winner |

boolean | If you won the previous round |

yourPlay |

string | The move you played last round |

theirPlay |

string | The move your opponent played last round |

roundSummary |

string | A text description of how the round ended, e.g. “paper covers rock” |

The messages the backend sends to the clients are personalized. The goal here was to keep complexity out of the client, it’s easy to render the “your” / “their” display consistently without worrying about who is the first or second player.

DynamoDB

The data is stored in a single DynamoDB table. The entire game state, including player moves, connection IDs, and scores, is actually stored in a single item per game!

{

"Expires": 1602221899,

"GameID": "4IRMC",

"PK": "GAME#4IRMC",

"Players": {

"a9kja9lonrg": {

"Address": "SlVhteXoPHcCFKQ=",

"ID": "a9kja9lonrg",

"Play": "paper",

"Round": 7,

"Score": 2

},

"v4rjxqc9qs": {

"Address": "SlVjXfddPHcCEyg=",

"ID": "v4rjxqc9qs",

"Play": "scissors",

"Round": 7,

"Score": 4

}

},

"Plays": 0,

"Round": 8,

"SK": "GAME#4IRMC",

"Type": "GameItem"

}

This data structure has some scaffolding for future plans. There is a Primary Key (PK) and a Sort Key (SK) that both have the same values: GAME#<game id>.

This is overkill for this particular app, but it leads to a nice extensibility path. For example, if I wanted to build a historical log of all the plays in a game, or enable chat, etc, all that data could all be stored with the same Game ID in the Primary Key, but with their own values for the Sort Key. That’s also why there is a Type field in the record, so when all records about the game are fetched, the types can be introspected.

The player field Address is the connection ID provided from API Gateway. It’s used when the user needs to be notified.

The player ID is a user-provided value, so that they can be ‘reconnected’ if their connection ID ever changes.

This sequence diagram shows the normal flow of players doing a round, and how it interacts with DynamoDB.

This takes advantage of the fact that DynamoDB has atomic writes. As you can see, both players set their personal move value, and (atomically) increment the Plays counter. The UpdateItem runs with ReturnValues: ALL_NEW, which means however the row changed after the atomic update, all those contents are returned.

That is excellent for a game like this, because it means we can introspect every play as the players make them – and if Plays=2, that’s guaranteed to be a complete round, with both player’s data, so a winner can be determined. Even if they play at exactly the same time, DynamoDB will still pick one write to be first and one write to be second.

Architecture Wrapup

So, that’s the key components of the Architecture:

- JSON over websocket for player actions and game state

- DynamoDB for state, and using the atomic writes to use player actions to drive the game state forward

- API Gateway for handling the connections, and Lambda for the logic

Deeper Dive

Having covered the high level, it’s time to get further in the weeds.

- Deployment – how the infrastructure is managed via SAM

- The Frontend – how the frontend app works

- The Backend Code – how the Go code is structured and runs

- Costs and Operational Overhead

Infrastructure and Deployment with SAM

I really like AWS SAM, the Serverless Application Model. It provides a very high level YAML syntax– like an extra-terse Cloudformation – to build a lot of common serverless app patterns.

The SAM template is available in full at rpsls/backend/template.yaml.

Only 157 lines to define the entire application is pretty impressive!

A few snippets to show roughly how it works. This sets up the API Gateway itself, and sets the protocol to WebSocket.

RPSLPWebSocket:

Type: AWS::ApiGatewayV2::Api

Properties:

Name: RPSLPWebSocket

ProtocolType: WEBSOCKET

RouteSelectionExpression: "$request.body.message"

Then, via a route, that’s wired up the the Lambda via an integration:

ConnectInteg:

Type: AWS::ApiGatewayV2::Integration

Properties:

ApiId: !Ref RPSLPWebSocket

Description: Connect Integration

IntegrationType: AWS_PROXY

IntegrationUri:

Fn::Sub: arn:aws:apigateway:${AWS::Region}:lambda:path/2015-03-31/functions/${RPSLPFunction.Arn}/invocations

That function is in turn defined as well. This app runs just fine in the smallest possible Lambda (128MB), usually running with only 48MB or so used. SAM also helps to wire up inputs for the lambda function, so the DynamoDB table name is available to it at runtime.

RPSLPFunction:

Type: AWS::Serverless::Function

Properties:

CodeUri: code/

Handler: handler

MemorySize: 128

Runtime: go1.x

Environment:

Variables:

TABLE_NAME: !Ref TableName

To actually deploy it, there’s a a small Makefile in the repo, which handles building the code, running tests, and then packaging and deploying the SAM template.

$ sam package --template-file template.yaml --output-template-file packaged.yaml --s3-bucket $(BUCKET_NAME)

$ sam deploy --template-file packaged.yaml --stack-name rockpaper-app --capabilities CAPABILITY_IAM

The Frontend

The frontend is a 177 line plain old javascript application. (No frameworks this time.)

The general architecture is entirely event-driven:

- When the page onLoad event fires, initialize the application, including trying to connect to the websocket

- When the connection is opened, either start a game, or join one (if you’re coming from a URL)

- When a play button (rock, paper, etc) is clicked, send a play message

- When a game state message comes from the backend, update the internal state and the display

- When the share button is clicked, the URL is copied to the clipboard

A few snippets of note:

This code handles the userId generation. It’s very simplistic but it works fine for this. It pulls it out of localStorage if it’s there, and otherwise it creates a new random ID and stores it back for next time.

_this.userId = localStorage.getItem("rockpaper-userid");

if(_this.userId == null) {

_this.userId = Math.random().toString(36).substr(2, 17);

localStorage.setItem("rockpaper-userid", _this.userId);

}

For many sorts of ‘real applications’ you’d probably have some sort of user authentication available instead – but I like this pattern for a lot of drop-in apps where you just want users to collaborate without actually wanting or needing to know anything about their actual identity, and with zero signup/setup friction.

I decided to go with a hand drawn feel, and I liked the idea of using the hand shapes for the game, especially since lizard and spock would be new to many people.

The images are actually photos of my hands that I took on my iPad, traced over in Pixelmator, and just saved that layer. Pretty nice way to get some royalty free art!

I also didn’t want to have two full copies of the images (if they were coming in from the left or the right), so figured out this little CSS hack to display them normally or mirrored via the transform property.

/** Set image in the UI for the hand gesture of the player.

* If the reverse flag is set, display the image flipped

* This makes it so the same set of images can be used

* to show them coming from the left or right player

*/

const setPlayImg = (element, url, reverse) => {

var img = document.createElement("img")

img.src = url

if (reverse) {

img.style.transform = "scaleX(-1)";

}

if(element.firstElementChild == null) {

element.appendChild(img)

} else {

element.replaceChild(img, element.firstElementChild)

}

}

Frontend is not my most comfortable development world, but every time I try and build something I’m amazed by how powerful the browser is as an execution environment. I’m sure there are lots of possible improvement to this code, but it works!

To actually build/minimize the code I’m using rollup.js powered, again, by a small Makefile.

Backend

First, testing.

There are two types of (fairly basic) tests in the repo. Go unit tests, and a javascript integration test which runs through the same flow that browser clients would.

Because DynamoDB was such an important thing to get correct here, I wanted to test against the real thing. What’s nice is that this is easy to do – the go code runs just as well on my laptop, and all that’s needed is for it to have IAM permissions and the right environment variable to be able to find the table.

dynamotest:

cd code/store/ && export TABLE_NAME=rpslp_connections && aws-vault exec serialized -- go test

Code Structure

The code is broken into a few internal packages:

main.go: Handler, gets the events from APIGW

notify

ws.go: a 'Notifier' interface, for messaging clients, and the APIGW Implementation of it

game

game.go: The abstract game logic (not tied to messages or storage)

game_test.go: Tests of the game logic

service: The API surface area

types.go: Definitions of JSON and Struct for the protocol

lambdaws.go: The code which handles all the websocket send/receive and interacts with the abstract Game

store:

dynamo_test.go: Tests of the dynamo store

dynamo.go: The dynamo store code

As with most lambda code, the main entry point is the Handler function.

It wires up the service, store, and notifier to provide the context to actually handle production messages.

func Handler(e events.APIGatewayWebsocketProxyRequest) (interface{}, error) {

sess := GetSession()

st := store.New(dynamodb.New(sess), os.Getenv("TABLE_NAME"))

no := notify.NewAPIGWNotifier(e.RequestContext.DomainName, e.RequestContext.Stage, sess)

svc := service.NewLambdaSvc(st, no)

switch e.RequestContext.RouteKey {

case "$connect":

return svc.Connect(e)

case "$disconnect":

return svc.Disconnect(e)

default:

return svc.Default(e)

}

}

There’s a lot of code, and hopefully it’s fairly readable. Let’s trace through the code which actually handles a play action by a user.

Inside the handler, Default is called, which sends over an events.APIGatewayWebsocketProxyRequest.

When there’s a play being made:

case "play":

err := s.Play(e.RequestContext.ConnectionID, message)

if err != nil {

return events.APIGatewayProxyResponse{

StatusCode: 400,

}, nil

}

it gets dispatched to the Play() method of the service.

Cutting out the error handling for brevity, but this is the key logic that implements the sequence diagram above.

// First, load the actual game object that matches this ID from DynamoDB

g, err := s.store.Load(message.GameID)

// Use that to create a GameContext, the abstract internal representation of a Game in progress:

gc, err := game.NewGameContext(message.UID, connectionID, g)

// apply the play the player just made to the GameContext:

err = gc.Play(message.Play)

// and then store the updated game context back in DynamoDB

err = s.store.StorePlay(gc)

// attempt to advance the game -- which can only happen if both players have now played

// This will increment the round, update the points, etc.

err = gc.Game.AdvanceGame()

// If that worked, store the updated game back in the DB

err = s.store.StoreRound(gc.Game)

// and then notify all the players a round is complete

s.NotifyPlayers(gc)

I ended up liking this design quite a bit. It would be really easy to drop a different store (replacing DynamoDB if needed) because the game code works with the interfaces – it’s only coupled by how it’s invoked in the Handler.

StorePlay is probably the most complex method.

// StorePlay takes a GameContext and stores the bits needed if a play has been made

// It updates the Game with the current status as well

func (s *Store) StorePlay(gc *game.GameContext) error {

input := &dynamodb.UpdateItemInput{

ExpressionAttributeValues: map[string]*dynamodb.AttributeValue{

":play": {

S: aws.String(gc.ActingPlayer.Play),

},

":count": {

N: aws.String("1"),

},

":round": {

N: aws.String(fmt.Sprintf("%d", gc.Game.Round)),

},

},

ExpressionAttributeNames: map[string]*string{

"#pxid": aws.String(gc.ActingPlayer.ID),

"#round": aws.String("Round"),

},

If you’re new to DynamoDB, there’s likely some mysterious things happening.

ExpressionAttributeValues are the values to set, e.g. :play is the move the player made (rock, paper, etc).

The ExpressionAttributeNames are dynamic items which end up in attribute (field) names. For example, #pxid is the hame for the current player’s ID. Since the DynamoDB item has a map of players by ID, that’s used to index it in the UpdateExpression.

ConditionExpression: aws.String(fmt.Sprintf("#round = :round and Players.#pxid.Round < :round")),

UpdateExpression: aws.String(fmt.Sprintf("SET Plays = Plays + :count, Players.#pxid.Play = :play, Players.#pxid.Round = :round")),

ReturnValues: aws.String("ALL_NEW"),

}

Putting that together forms the UpdateExpression, which enables that atomic operation to work like a laser beam on the item.

There’s also a ConditionExpression which ensures plays for old rounds, or attempts to change a play for the current round, are discarded. There’s a strict no takebacksies policy here.

As you can see, this is extremely safe in the face of the other player playing simultaneously. The only fields being set are for this specific player, and otherwise they are an increment.

Also, ReturnValues are used to fetch the latest version of the Item after all these updates.

Here’s those values being loaded and then integrated into the game object.

result, err := s.d.UpdateItem(input)

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("got an error storing a dynamo play\n")

fmt.Println(err.Error())

return err

}

item := GameItem{}

err = dynamodbattribute.UnmarshalMap(result.Attributes, &item)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("unmarshal error: unable to retrieve game values")

fmt.Printf(err.Error())

return err

}

UpdateGameFromItem(gc.Game, &item)

return nil

}

And that’s it!

Cost and operational modeling

How would this work out cost-wise for building a real game?

The relevant charges, ignoring the free tier (and using us-west-2 pricing):

- API Gateway:

- $1/million websocket messages

- $0.25/million connection-minutes

- DynamoDB

- $1.25/million write request units

- $0.25/million read request units

- Lambda:

- $0.20/million requests

- $0.0000002083/100ms for a 128MB lambda

Let’s assume an average game would take 5 minutes of time before people got bored, and that they’d play 20 rounds.

| Action | Messages | DynamoDB Writes | DynamoDB Reads | Lambda Invocations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creating a game | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Joining a game | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Setup Subtotal | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| First play | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Second play | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Round Subtotal | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 20 Round Subtotal | 80 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

So one game will total:

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| 10 connection-minutes | $0.0000025 |

| 84 websocket messages | $0.000084 |

| 42 DynamoDB writes | $0.0000525 |

| 42 DynamoDB reads | $0.0000105 |

| 44 lambda invocations | $0.0000088 |

| 44 lambda 100ms @128mb | $0.0000091652 |

| Grand Total | $0.0001674652 |

In other words, for $1, you can play about 6,000 games.

For a lot of use cases, this is going to be far more attractive than even the cheapest, smallest t-type instance. A t3a.nano costs $3.38/mo plus whatever you spend on EBS, and that only includes a 1h 12m burst. So if you were hosting over 20,000 games a month, you might be able to save some money by doing a tiny instance – assuming it didn’t go down or run out of resources during a period of load.

I love how dependable the serverless stack is. I was working on this app off and on for a few months, and then left it in the corner since about May. (My response to lockdown was apparently to rediscover what’s been up with videogames for the last 20 years. Turns out, a bunch!) It was impressive, but not surprising, to be able to open the web app last night and have it be working perfectly after being left alone for 4 months – accruing exactly $0/month in costs.

That’s probably enough for now, again, the full source (including infrastructure) is at jbarratt/rpsls. Feel free to get in touch via email or pull request with comments, questions, or things I’ve gotten terribly wrong.