If you have worked in technology companies for a while, you’ve probably “processed” in many different ways. You may have used with Agile, Scrum, Lean, Kanban, SAFe, eXtreme Programming, and many more.

There are lots of reasons to choose a given framework. Often it’s something that’s been standardized in a department or a company, and individual developers or team leads may not have anything to say about it. Other companies are more concerned about the results and output, and don’t focus on how things work internally to the team.

In this post I’ll share my favorite way I’ve found, so far, to organize a team. We called it “TeamOS” – the set of processes and practices used to measure results, get work done, and to change process over time.

I’m not saying it’s the best, or that other ways are wrong or worse – it’s just a description of how the team worked, with some background for how we chose it. I hope it’s helpful to others out there who are still trying to uncover better ways of developing software. (In fact, I am not currently even running a team, this writeup is by request of a friend who wanted to hear more about this approach.)

Team and Process Constraints

What is the ultimate purpose of team process? Why not just go get work done?

Keeping “the point” in mind is important both for crafting the process initially, as well as a way to vet proposed changes and focus improvement efforts.

Team process selection is a familiar shaped problem to lots of others we face in engineering. You’re trying to meet many different goals with it, and there end up being a lot of tradeoffs to be made between them. It’s hard to change how work gets done without impacting them all.

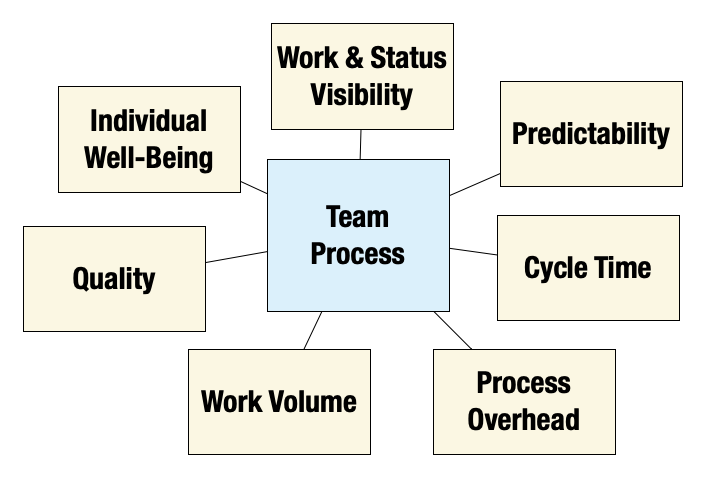

Here’s a partial list that seems to come up often:

- Predictability:, or “quality of forecasts.” The business is hungry to have a trusted prediction of “when it will be done”, because it enables forecasting revenue, coordinating marketing around releases, and ensuring cross-team dependencies can be met on time.

- Visibility: How much can everyone self-serve to find the information they need? Team members discovering work to be done, and other stakeholders discovering (reliable) status they need?

- Quality: (of work product) is also essential. The process should support, and not detract from the ability to ship operable, well architected, reliable, low-defect, low-tech debt, secure, scalable software that meets the functional and non-functional requirements of the business.

- Individual Well-Being: Do the people on the team have a good work-life balance? Have we minimized frustration? Are they being given the opportunity to grow and learn, as well as exercise mastery? Are they being respected? Is their time being wasted? Are they able to ‘flow’, to focus in extended blocks of time? Can they do their jobs without fear (when doing everything from deploying to giving feedback?)

- Work Volume: How much do we actually get done? How much value did we produce in a given unit of time?

- Time To Value/Cycle time: How long does it take us to get something to providing actual value to the business from when it comes in? (See below for more on ‘Value’)

- Minimized Overheads: how much of our time is being taken up not directly contributing to value? (Ceremonies, slow build/deploy/test processes, etc.)

While it’s impossible to optimize for 7+ constraints, when considering process change, it can provide a rich method for evaluation. For example, “we should work 6 days a week” would theoretically increase work volume, but would be a substantial decrease in “Well-Being” and “Quality”.

TeamOS: Definition and Key Ideas

We called our (meta)process “TeamOS”, because like an Operating System, it is what keeps things moving, but it’s also upgradable and changeable over time, as the team learns and grows, or as the kind of work that’s being handled changes.

This document, or an even more simplified version of it, would be my “starter kit” if I was launching a new team today. I’d expect all of it – even the constraints and ideas – to evolve over time as needed.

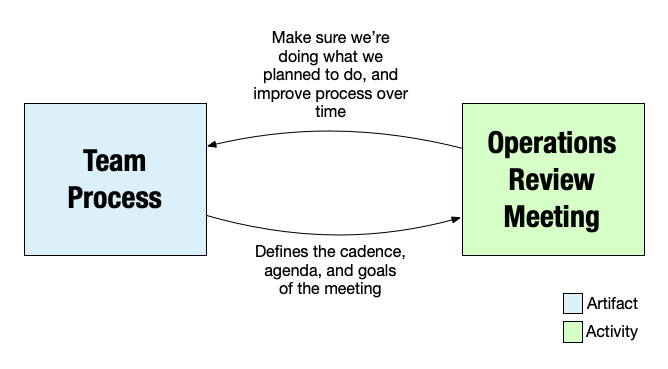

The Foundation: A Machine for Evolving Process

The fundamental tool for building a process is having something that you can call “the process”. In this case, we need

- Some kind of source of truth for the decisions about how to run the team

- A periodic way to ensure we’re running in accordance with our decisions about how to work, and a way to adapt and improve over time.

So for a team, some options to store this might be

- A wiki page or Google Doc

- A set of Team Decision Records in a git repository, with changes proposed by pull request

The discussions of alignment to the process and improvement might be a kanban-style periodic Operations Review, a post-sprint Retrospective meeting, or even use something asynchronous like a chatbot.

The key is to have the process written down, to have a way to improve it, and to make sure it’s actually being used.

Some ideas about Teams and Process

These ideas have informed a lot of the practices I have found helpful, and they form some of the “why” underneath the tactical “whats”. So, they’re worth being explicit about. Little of this will be news if you’ve explored Lean Software and Kanban.

Idea 1: The Team Owns The Process

We hold teams accountable for their results. One of the most powerful tools at their disposal to improve the quality of those results is how they work. While there are plenty of things they’ll be required to do (from compliance to SLAs), standardizing the process itself leads to a ‘lowest common denominator’ solution.

Teams vary in size, personality, composition, workload, on-call burden, technology stacks, and many other dimensions. Expecting a deeply standardized way of working to work across non-standard teams and problems is trading mediocrity for consistency.

Idea 2: Incremental, Iterative Value, and Short Feedback Loops

“Ship Working Software” is easy to pay lip service to, but only can happen when it’s planned for from the beginning.

This pays off in so many ways when done properly, though. It gives early opportunity for stakeholders, from product to dependent teams to groups like security, quality and architecture – to give feedback when it is much cheaper to incorporate. Even architecture should be incremental.

Rapid cadences give the team the opportunity to learn themselves, and provides the satisfaction of actually completing work. If I ship some working software on a Thursday evening, I feel great. If I commit a feature to a branch which probably won’t land for a month, it has far lower emotional weight.

Want to speed up development? Shorten feedback loops!

— Henrik Joreteg (@HenrikJoreteg) November 16, 2018

1. Design to dev

2. Pushes to deploys

3. Code change to seeing result on the screen

4. Lint to catch errors as you type

5. Empower devs to make decisions then ask for feedback instead of waiting for product

6. Smaller teams

Idea 3: Focus on Delivering Value // Inventory Is Waste

The reason we have teams at all is to deliver business value. Depending on the work a team is chartered with, that may take many forms; anything from a customer-facing feature release to completing an internal audit. But a completed audit has value; an in-progress audit has not yet ‘become value.’ A completed, deployed feature is value; a feature under design, or development, or test, or waiting for a deploy – is not yet value.

So whatever value looks like for a given piece of work, getting that across the line is a priority.

All undelivered value, work in any other state of conception, execution, or delay – is waste. Some people have a strong reaction to the word waste. It’s more precise to say that before work becomes value, it has a higher potential to become waste (if it’s never turned into value), or to cause waste, because we’re having to spend more energy working with and around it while delivering value. As a principle, the higher the ratio of “value to inventory” is, the less waste there is likely to be.

Idea 4: Maximize Flow

Flow can be thought of in two ways, and it’s important to try and maximize both.

Mental Flow

The state of flow is incredibly valuable – as it is where so much of the “actually valuable to the business” work happens. We should seek to maximize both the per-developer mental state of focus, as well as the continuous delivery of value.

Flow is when a person ① is engaged in a doable task, ② is able to focus, ③ has a clear goal, ④ receives immediate feedback, ⑤ moves without worrying, ⑥ has a sense of control, ⑦ has suspended the sense of self, and ⑧ has temporarily lost a sense of time. – Csikszentmihalyi, 1990

Getting our work, and our environments, into a position which enables these mental states is essential for increasing both the amount of value developers deliver, but also the quality of that work, and their happiness and fulfillment while they do so.

Value Delivery Flow

Lean talks about the broader sense of flow a lot. We want each bit of work to move through each stage of the concept to value stream with the mimumum disruption. And team members should be focusing on the big picture, getting things across the line from waste to value, wherever things might be backing up.

The artificial boundary of “the sprint” in Scrum is a good example of such a disruption. It can be very valuable, when it’s well utilized for coordinating with the business, e.g. “showing the product manager the demo so they can re-orient the next sprint.” I often see it used without those practices – so it only adds stress and busywork, and reduces quality. We also don’t want developers to rush to hit a sprint deadline, leaving technical debt behind, and then doing extra work to ‘carry over’ cleanups into the next sprint. Maximize Flow.

Idea 5: Make Work Big And Visible.

Having a very clear and tactical view of your work in progress is essential to productivity.

This visualization can take lots of forms, and it’s one of the highest yield places for improvement experiments. The visualization of work should serve the team and the stakeholders needs. Clear organization helps with:

- Developer focus: being able to extablish “this is what needs to be done now, and next”, without needing to interrupt others

- Stakeholder awareness, without needing meetings or to interrupt the team

- Visualizing bottlenecks (“mmm, we have a lot of stuff waiting for QA, let’s tag team” or “that ticket has been stuck there for 3 days, maybe we need to rethink that.”)

TeamOS: Practices

Ok, how should a team apply those ideas? Here’s a solid starting point, which can be evolved from as the team desires.

The Board

A basic Kanban-style board is a great starting point. It should have the least possible columns which empower the team to work asynchronously. “To Do, Doing, Done” is fine if that works well. But a more complete flow might be “Dev Ready, In Development, PR Ready, QA ready, In QA, Deployed”. Teams should adapt to their requirements and flow.

It’s also good to have a visualization of ticket progress. Jira has a dot mechanism which can identify how many days a ticket has been in place. If the team has a goal (e.g. ‘tickets shouldn’t take longer than 2 business days’) they can be easily noticed as they age, and possibly replanned.

It is also really helpful to have an overall WIP limit for cards on the entire board, for example, “4 cards/developer”. On a team of 5, 20 cards is likely plenty to visualize all the work that is truly in progress. Clearly the broader backlog is probably going to be larger, but there’s no reason to have that “inventory” be making it harder to comprehend the day to day tactical needs.

WIP Limits

“WIP” stands for Work In Progress. A WIP Limit can be applied in many different areas. It’s a useful tool to help limit “inventory~=waste” issues and also increase visibility and focus by reducing clutter.

Example WIP limits:

- There can be only 8 tasks in the “In Progress” column

- There can only be 30 cards on the entire board

- There can be only 2 change experiments running

- There can be only 4 items in the tech debt penalty box

They can be either strictly enforced (like a guardrail) or just used to flag issues (like a rumble strip). Typically, they’ll drive a conversation. “I want to pull in a task but we hit the WIP limit.” “Is anyone close to finishing something that could use Mary’s help in pairing?”

The Standup

With a trusted board, Standups can invert the Scrum order, in which team members are asked about what was done yesterday, their plans for today, and if there are blockers.

The board should reflect what was done, the board should visually show blockers, and most importantly, the board should dictate what any given team member should plan to do!

Standup Template:

- Team members ensure that the board reflects reality, and fix it if not.

- Check for any critical/expedited tasks, if the team uses those, and ensure they are getting moved as quickly as possible.

- Starting at the right hand side of the board (“value”), pull tasks over. Look for opportunities where collaboration can help move things into the ‘Done’ column.

- If a task has been stuck for too long (perhaps 3 days), discuss if it will be moving that day, or if a breakout is needed to reconsider the approach. (Note: Jira has an optional ability to display time a ticket has been in a column via dots.)

- If the capacity of the “To Do” column is too low, do some ‘demand planning’. (see below)

- Ensure everyone has an actionable task assigned to them

And that’s it. With a clean board, standups can sometimes take only minutes, or happen asynchronously.

Key Metrics

There are several key metrics to consider.

- Cycle Time: How long does it take to bring a task from (To Do) to (Done)?

- Throughput, or Work Volume: How many tasks arrive in Done over a given time period?

- Scheduled / Emergent Ratio: What tickets came from our longer term planning, and which from some other means? (Operational issues, stakeholder needs, or other urgent sources)

Usually these numbers are based on “work hours” or “work days.”

Both numbers end up falling on a range. Much like operational metrics, the means and medians are not very useful. Consider 5 tickets which took [1, 3, 1, 28, 2] days to complete. What would you expect the next ticket to take? The average time is 12.6 days. But it’s probably more meaningful to say “80% of the time we’re getting tickets done in 3 days or less.”

This is also helpful when setting planning expectations, as those percentile measures map fairly reasonably onto confidence of estimates for stakeholders, as we will see.

Planning

There are many approaches to planning and sizing, and this is a particularly rich area for teams to experiment and innovate to match their workloads.

After trying many variations, my default starting point is:

- Tasks are work which

- Have distinct business value (can be independently moved to Done, generally ‘deployed’)

- A developer believes are completable within a single work day

- Epics are collections of tasks

- Which have a business-level value which can be communicated about, e.g. “pagination of search results”, or “reducing failover time to 1 hour”

- Have a “Fanout Limit”, or a maximum number of tasks (typically ~10) which can be attached to them.

Larger business initiatives can be planned out to a series of Epics; Epics can be planned out to tasks. If needed, Epics/Stories/Tasks can be used, or other terms, to have more of a hierarchy. Consistency within the team is the important attribute.

The process of “tasking out an epic” into expected-single-day-executable tasks has proved to drive many crucial conversations.

- If we can’t conceive of how to get something ‘shippable’ done within a day, that’s a smell, and a sign that the architecture should be more flexible, or that we’re thinking of the problem too “layer caked” or “waterfally.”

- The key is to ship business value; sometimes that doesn’t literally take the form of software. It may be ‘complete an intro to AWS course’, where the value is that you know more about what you’re doing.

- Getting to the finer details increases the quality of initial plans, as it forces a discussion at a more granular level. “Oh, crud, we’re going to need a test user for that, that’s a day right there, and we’re going to need to get the container harness up and running too, that’s another day…”

Story Mapping

Story Mapping is a useful tool for providing clarity and visibility, as well as thinking through the hard problem of how to deliver small bits of work which are actually valuable.

If you think of a story as a ‘leaf’, a lot of times developers get a bunch of work as a ‘bag of leaves’. Story maps provide the context (‘the tree’) that the leaves hang off of.

Because a story map is built around the actual workflows that drive a feature, it is a good way to pick and choose how much something needs to be done at a given level. As a trivial example, we may build a service which needs robust authentication. An early release may have no authentication, but be released into a pre-production area for other team members to begin integration work against.

Demand Planning

Generally, in order to keep the board legible (and honor the WIP limit), Epics are kept untasked until the board starts to run dry. Tasking Just In Time is helpful for several reasons:

- Planning can be done with just the product owner and the members of the team who it’s anticipated (or selected in standup) will be involved in that effort. This leaves the rest of the team free to focus on delivering value.

- Doing plans just in time means taking advantage of the latest state of the team. “We decided not to use service X anymore” or “we can use the test harness we got running yesterday”.

- The knowledge of what work was planned still tends to be fresh in the minds of the planners, leading to fewer “ok, but why did we put that in the acceptance criteria” or “what on earth did we mean by that acronym?” conversations.

“Just In Time” doesn’t need to mean literally the day of, work can be tasked out within a safety margin; since a ticket (ideally) represents a person-day of work, having 3 tasked epics likely represents well over a work-week for a perfectly executing team. The size of the planned buffer can be tuned as the team retrospects.

Change Experiments

How should the team change process and practices over time? Typically this is done in an ad-hoc fashion, driven by Retrospectives. “Do we want to try X?” “Ok, I’ll take an action.”

Change Experiments wraps some more structure around that familiar process. Any proposed change needs a few things:

- How long will we run it for?

- What is the hypothesis? (If we do X, we expect to see Y)

- How will we measure it?

Some of the best measurements can come from the constraints discussed at the top of the post. (Predictability, Visibility, Quality, Individual Well-Being, Work Volume, Time to Value/Cycle Time, Minimized Overheads). Increases in one or more of the constraints, without decreases in the others, is usually what we’re looking for. Some constraints are measured subjectively, but that can be ok – it at least provides a shared frame.

An example experiment template:

- Change Experiment: New Standup Time

- How Long: 4 weeks (Until operations review on 8/22)

- What’s the hypothesis? We expect that having standup at 2:45pm is better use of our team’s energy level, and will provide more focus in the morning, while helping refocus the team for the final “leg” of the day.

- How Will We Measure It? We should see an increase in throughput and a decrease in cycle time by at least 2% over the prior 12 week window. We should also have a quorum of the team thinking that our well-being is improved. Attendance should be as good or better as it was in the past.

After the experiment window closes, teams can choose to accept, reject, or modify and run another experiment. If they reject it, they can store “what we learned” in the team notes.

Change is a two edged sword, though. We only improve through change, but change can be very disruptive to flow. It’s important to discriminate carefully about how many changes to be experimenting at once, another useful application of a WIP Limit. (And, of course, changes in the change WIP limit can be a change that’s experimented with!)

Example changes may include:

- Changing the board: columns, swimlanes, WIP limits, ticket types (e.g. bug/expedite/work classes)

- Changing timing, cadences, durations, agendas of periodic meetings

- Altering any other working methods (testing, CI/CD tools, documentation standards, code review techniques, pairing, core hours, focus silos, working techniques between engineering and product, on-call strategies, how to celebrate birthdays, slack bots, etc etc etc.)

- Changing where and how the process document is stored.

Operations Reviews or Retrospectives

This is an example of the meeting referred to as foundational – the one where it’s ensured that the process is being followed, to look at how the team is perfoming objectively and subjectively, and to make changes and improvements.

- These meetings shouldd be planned on some cadence which is useful to the team. Without sprints, there is no natural boundary at which to “retrospect.” I usually go with something like ’the first Tuesday of the month.'

- The meetings should be heavily enriched by data – team metrics like cycle time/CFDs, service health, on-call information, upcoming vacation schedules, etc.

A typical operations review agenda would be:

- Refresh the team on any Change Experiments in progress

- Review “value delivered” since the last review. Hopefully this is an opportunity to say “holy cow, look at everything we got done” and not “holy cow, is that all we got done?”

- Review key metrics since the last review.

- How has the cycle time changed? If we have slowed or sped up, any ideas as to why?

- How much throughput have we pushed? How much have our tasks/day volumes changed, and any ideas as to why?

- How much ‘inventory’ are we generally carrying? This can be seen from the Cumulative Flow Diagram. Are we bottlenecking in any areas consistently?

- Check in on the other key constraints

- How are people feeling (If you’re nostalgic for fist of 5, here’s a good place to do that.)

- How has the quality been? Any incidents of note? How is the on-call burden?

- How well has the team hit delivery targets

- How is the visibility of the board? Can we understand what’s going on at a glance?

- Decide to adopt/adapt/reject change experiments that have ‘expired’

- Discuss which, if any, new change experiments to begin

Tech Debt Penalty Box

As a side effect of trying to build incrementally, sometimes things can’t be done to the desired level of quality as a first pass.

If doing work that we know needs future work, these tickets (or even epics) would generate an additional technical debt ticket, stored out of band (for example, in a google doc). We don’t want it to be tracked in a way which impacts either the visibility of the board, or the metrics derived from it.

This technical debt ‘penalty box’ would have it’s own WIP limit. So if we’re doing some demand planning, and notice a debt item is being created that pushes us over the limit – we have to remove another item and prioritize it before a new one can be added.

Forecasting

Estimates are terrible. Nearly every software developer dislikes them. They are unreliable for the business as well, and even so, can take a huge amount of time and mental/emotional energy to develop. There’s even been an ongoing debate (#noestimates/#estimates) for years about if they should exist and how they’re useful.

Ok, but without estimates, how can we meet the understandable and important business need for predictability? Estimating may be hard, but as professional engineers, it’s still our responsibility.

The answer, as usual, lies in the data. The science of forecasting is well-established, especially in the IT industry, where it’s been heavily invested in for things like capacity planning, where the price of both under and overestimation can be very high.

If a team has a stable planning method, as described above – “epics are expected to be <= 10 tasks of work, tasks are expected to be completed within 1 business day” – within a reasonably short amount of time actually doing work, we can start to provide some forecasting.

- We can calculate how many tasks are ultimately attached to an epic (which will probably grow beyond whatever initial limits we set, since the scope wants to creep)

- There is data for how much throughput the team is actually producing (probably less than 1/ticket/developer/day)

- There are metrics on cycle time, which gives the range of expected lead times

- We can see over time the percentage of ‘bandwidth’ the team has available for planned work vs emergent work from ongoing service support

Combining these things together can provide some some forecasts. There won’t be a standard formula, since projects vary in how threaded they can be, and some require specific expertise, but trying to make an estimate based on work done in the past, how work expands, and how well the team progresses on planned vs emergent work can be a very powerful approach. Most of the work emerges from the actual (usable) exercise of planning the work in the first place. Example:

Based on our initial breakdown of this work into tasks, we identified 3 epics of 7 tasks each. This covers a wide variety of skill areas and doesn’t have a lot of internal interdependencies. Our task expansion rate is around 22%, so this turns into an expected 25 tasks. The team’s 80% throughput rate is 8 planned tasks/week, so the estimate is 3.125 weeks.

TeamOS v0.0.2a

So, if I was starting a team today, I’d start here, fully expecting to end up somewhere else.

- A foundational document and a periodic, data-enriched meeting to review and improve

- A collection of tools

- A Board with WIP limits

- Change Experiments

- Tech Debt Penalty Box

- A set of practices

- Board-oriented standup

- Story mapping

- Demand planning and forecasted estimates

I’d love to hear from folks (who aren’t vendors) about their experiences here. What else should be on this list?

Photo by Lala Azizli on Unsplash