Recently, one of the teams I work with selected Envoy as a core component for a system they were building. I’d been impressed for some time by presentations on it, and the number of open source tools which had included it or built around it, but hadn’t actually explored it in any depth.

I was especially curious about how to use it in the edge proxy mode, essentially as a more modern and programmable component that historically I’d have used nginx for. The result was a small dockerized playground which implements this design.

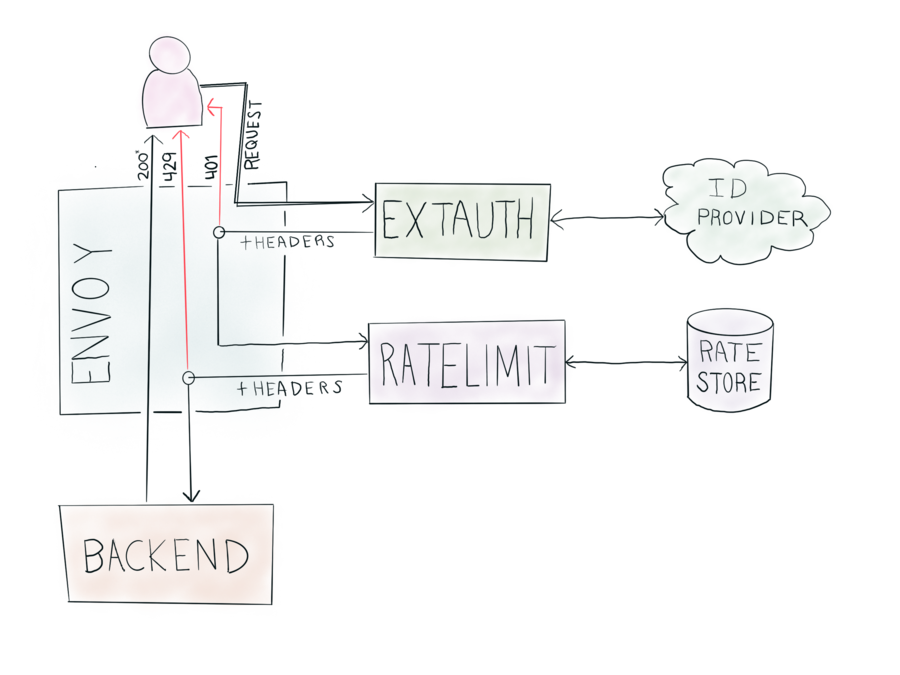

The request flows through the system in stages:

- A client sends a resource request to Envoy (in a gateway role)

- Using Envoy’s External Authorizer interface:

- Authenticate the call, rejecting it if invalid

- Set custom headers which can be used for rate limiting

- Depending on the route, supply different information to use for rate limiting

- Using the Ratelimiter interface, apply a rate limit, rejecting if over-limit

- Finally, pass to a backend, and return the response to the client

With this limited experience I can say Envoy more than lived up to my expectations. I found the documentation complete, but sometimes terse, which is one of the reasons I wanted to write this up – it was hard to find complete examples of this kind of pattern, so hopefully if you’re reading this, it saves you some effort!

For the rest of this post I’ll be going layer by layer through how each part of this stack works.

The Docker Environment

I’m using docker-compose here, as it provides simple orchestration around building and running a stack of containers, and the unified log view is very helpful.

There are 5 containers:

envoy, which, no shock, is … envoyredis, used to store the rate limit service’s dataextauth, a custom Go app which implements Envoy’s gRPC spec for external authorizationratelimit, Lyft’s open source rate limiter service which implements the Envoy gRPC spec for rate limitingbackend, a custom Go app which is essentially “hello world”, and also prints the headers it receives for troubleshooting ease.

docker-compose also creates a network (envoymesh) for all the services to share, and exposes various ports. The most important one ends up being 8010 (or localhost:8010 on most docker machines) which is the public HTTP endpoint.

To get it running, clone the repo. You’ll also need a local copy of Lyft’s ratelimit. Submodules would have been good here, but for a PoC it just as easy to git clone git@github.com:lyft/ratelimit.git.

I had to make some manual tweaks to the ratelimit codebase to get it to build – which may be operator error:

mkdir ratelimit/vendor(theDockerfileexpects it to exist already)- add a

COPY proto prototo theDockerfilewith the rest of theCOPYstatements

After getting the code in place, run docker-compose up. The first one will take some time as it builds everything.

You can ensure that the full stack is working with a simple curl, which also shows traces of all the moving parts.

- Instead of integrating with a true identity provider, all bearer tokens which are 3 characters long are considered to be valid.

- The authorizer sets a header (

X-Ext-Auth-Ratelimit) which can be used for unique per-token rate limiting - In the envoy config, the Authorization header is stripped, so sensitive identity information is not pushed to backends

$ curl -v -H "Authorization: Bearer foo" http://localhost:8010/

> GET / HTTP/1.1

> Authorization: Bearer foo

>

< HTTP/1.1 200 OK

< date: Tue, 21 May 2019 00:23:12 GMT

< content-length: 270

< content-type: text/plain; charset=utf-8

< x-envoy-upstream-service-time: 0

< server: envoy

Oh, Hello!

# The backend got these headers with the request

X-Request-Id: 6c03f5f4-e580-4d8f-aee1-7e62ba2c9b30

X-Ext-Auth-Ratelimit: LCa0a2j/xo/5m0U8HTBBNBNCLXBkg7+g+YpeiGJm564=

X-Envoy-Expected-Rq-Timeout-Ms: 15000

X-Forwarded-Proto: http

Defining the backend

The backend is a very simple Go app running in a container.

It shows up (cleverly named backend) a few times in the envoy.yaml config file.

First, it’s defined as a ‘cluster’ (though, as a single container, it’s not much of a cluster.)

clusters:

- name: backend

connect_timeout: 0.25s

type: STRICT_DNS

lb_policy: round_robin

load_assignment:

cluster_name: backend

endpoints:

- lb_endpoints:

- endpoint:

address:

socket_address:

address: backend

port_value: 8123

This is an example of where the Envoy config can take some time to understand. For a simple “single host” backend it takes some pretty significant boilerplate. But, it’s also incredibly powerful. We’re able to define how to look up the host, how they should be load balanced, more than one cluster, more than one load balancer within a cluster, and more than one endpoint within that. It’s entirely possible that this definition can be simplified, but this version works.

It’s nice and consistent that the cluster definition is the same when defining either

- one of the services that Envoy will proxy to, or

- one of the ‘helper’ services that Envoy filters communicate with, such as the authorizer and rate limiter.

It’s also helpful that clusters (and the whole config) are defined with well-managed data structures, that are actually defined as protobufs. This means managing Envoy can be done fairly consistently when you’re configuring it with YAML files, or at runtime through the configuration interface.

So, now that the backend is defined, it’s time to get it some traffic, and that’s done via routes.

route_config:

name: local_route

virtual_hosts:

- name: local_service

domains: ["*"]

routes:

- match: { prefix: "/" }

route:

cluster: backend

Again, a decent bit of data structure to say “send all traffic to the cluster I defined called backend”, but as we’ll see when it’s time to add in conditional rate limiting, it provides similarly useful places to hook in additional configuration.

Custom External Authorizer

Envoy has a built in filter module for external authorization.

http_filters:

- name: envoy.ext_authz

config:

grpc_service:

envoy_grpc:

cluster_name: extauth

This fragment of config says to call a gRPC service which is running at a cluster (defined the same as the backend above) called extauth.

I am so happy about 2 quasi-recent developments which make this so easy to build – Go modules and Docker multi-stage builds.

Building a slim container, with just alpine and the binary of a Go app, only takes this little fragment of Dockerfile. Yes, please.

FROM golang:latest as builder

COPY . /ext-auth-poc

WORKDIR /ext-auth-poc

ENV GO111MODULE=on

RUN CGO_ENABLED=0 GOOOS=linux go build -o ext-auth-poc

FROM alpine:latest

WORKDIR /root/

COPY --from=builder /ext-auth-poc .

CMD ["./ext-auth-poc"]

Ok, so how do we build the app? For Go services, Envoy has made things very clean and straightforward.

The types are includable from the Envoy repository, e.g.

auth "github.com/envoyproxy/go-control-plane/envoy/service/auth/v2"

which define things like an CheckRequest and CheckResponse.

This allows constructing and returning the proper responses based on what we need to do. Here’s the core of the successful path, for example:

// inject a header that can be used for future rate limiting

func (a *AuthorizationServer) Check(ctx context.Context, req *auth.CheckRequest) (*auth.CheckResponse, error) {

...

// valid tokens have exactly 3 characters. #secure.

// Normally this is where you'd go check with the system that knows if it's a valid token.

if len(token) == 3 {

return &auth.CheckResponse{

Status: &rpc.Status{

Code: int32(rpc.OK),

},

HttpResponse: &auth.CheckResponse_OkResponse{

OkResponse: &auth.OkHttpResponse{

Headers: []*core.HeaderValueOption{

{

Header: &core.HeaderValue{

Key: "x-ext-auth-ratelimit",

Value: tokenSha,

},

},

},

},

},

}, nil

}

}

The ability to write arbitrary code at this point of the request cycle is very powerful, because adding headers here can be used for all kinds of decisions, including routing and (as we’re doing here) rate limiting.

Rate Limiting

Rate Limiting can be done with any service implementing the Rate Limiter interface. Thankfully, Lyft has provided a really nice one which has a straightforward but powerful config – for a lot of use cases, it’d probably be more than sufficient to use. (Lyft’s Ratelimiter)

Just like with the external authorizer, there’s some Envoy configuration to enable an external rate limiting service. You define the cluster, and then you enable the envoy.rate_limit filter.

- name: envoy.rate_limit

config:

domain: backend

stage: 0

failure_mode_deny: false

rate_limit_service:

grpc_service:

envoy_grpc:

cluster_name: rate_limit_cluster

timeout: 0.25s

To get envoy to rate limit, you have to tell it what to limit on. This can by done per route, which is super helpful. Envoy can be configured to send key/value pairs to the ratelimiter service.

Here, 2 routes are defined:

/slowpath, which sends overgeneric_key:slowpath/(everything else), which sends overratelimitkey:$x-ext-auth-ratelimitandpath:$path– where the values with the$are whatever values those headers have.

- name: local_service

domains: ["*"]

routes:

- match: { prefix: "/slowpath" }

route:

cluster: backend

rate_limits:

- stage: 0

actions:

- {generic_key: {"descriptor_value": "slowpath"}}

- match: { prefix: "/" }

route:

cluster: backend

rate_limits:

- stage: 0

actions:

- {request_headers: {header_name: "x-ext-auth-ratelimit", descriptor_key: "ratelimitkey"}}

- {request_headers: {header_name: ":path", descriptor_key: "path"}}

When you are using Lyft’s ratelimiter, the actual config is pretty elegant.

---

domain: backend

descriptors:

- key: generic_key

value: slowpath

rate_limit:

requests_per_unit: 1

unit: second

- key: ratelimitkey

descriptors:

- key: path

rate_limit:

requests_per_unit: 2

unit: second

Everything is happening within the backend domain (which is an arbitrary string, defined when enabling the rate limit filter). There are 2 descriptors being looked for, generic_key, and ratelimitkey.

When there’s a value provided, that ends up being a static entry – like slowpath – which applies to all requests. When no value: is provided, it uses the key and the value provided to build a composite key. They can also be nested, as here. The heirarchy for the second block is ratelimitkey/path.

So this configuration should do 2 things:

- Globally limit

slowpathto 1 request per second - Enable all users to have 2 requests per second, per path

And that’s about it!

In combination with the ability to set any header value desired from within the custom authorizer code, this ends up being an excellent way to rate limit on pretty much anything desired. Some interesting options include:

- User or Account information

- The specific authentication information (which API key/token was used)

- A source IP

- User-varying information, enabling things like having customers pay for different rate limits or issue temporary overrides

- A computed fraud/risk categorization

Testing and Verification

It was fun to put this all together, but I wanted to make sure it, you know, worked and stuff.

I ended up with one of the stranger go test files of my life, but I’ll take it.

In short, it’s Go table driven testing, plus vegeta used as a library, to validate that all the authorization and ratelimiting works as intended.

First, some vegeta targets are set up with various characteristics. This one is making a call to /test with a valid API key, and there are 5 others for various combinations of what paths to call, keys to use, and if the keys are valid.

// An authenticated path

authedTargetA := vegeta.Target{

Method: "GET",

URL: "http://localhost:8010/test",

Header: http.Header{

"Authorization": []string{"Bearer foo"},

},

}

Given that, some tests can then be run, like so:

testCases := []struct {

desc string

okPct float64

targets []vegeta.Target

}{

{"single authed path, target 2qps", 0.20, []vegeta.Target{authedTargetA}},

{"2 authed paths, single user, target 4qps", 0.40, []vegeta.Target{authedTargetA, authedTargetB}},

{"1 authed paths, dual user, target 4qps", 0.40, []vegeta.Target{authedTargetA, otherAuthTarget}},

{"slow path, target 1qps", 0.1, []vegeta.Target{slowTarget}},

{"unauthed, target 0qps", 0.0, []vegeta.Target{unauthedTarget}},

}

Each test gets a description, an expected ‘success percentage’, and the blend of one or more targets to run. All the tests run at 10 queries per second, so if the rate limit should be 2 queries per second, that gives an expected success rate of 20%. (0.20).

So to actually run the tests with vegeta:

func runTest(okPct float64, tgts ...vegeta.Target) (ok bool, text string) {

rate := vegeta.Rate{Freq: 10, Per: time.Second}

duration := 10 * time.Second

targeter := vegeta.NewStaticTargeter(tgts...)

attacker := vegeta.NewAttacker()

var metrics vegeta.Metrics

for res := range attacker.Attack(targeter, rate, duration, "test") {

metrics.Add(res)

}

metrics.Close()

if closeEnough(metrics.Success, okPct) {

return true, fmt.Sprintf("Got %0.2f which was close enough to %0.2f\n", metrics.Success, okPct)

}

return false, fmt.Sprintf("Error: Got %0.2f which was too far from %0.2f\n", metrics.Success, okPct)

}

This ends up being really exciting. A simple test definition can actually test that various rate limiting scenarios actually limit the rate.

The tests do run for 10 seconds. I tested with different rates and because it takes a bit for the rate limiting to start tracking, the data had more fuzz in it with shorter tests.

This whole test suite runs fairly easily:

$ make test

cd loadtest && go test -v

=== RUN TestEnvoyStack

=== RUN TestEnvoyStack/single_authed_path,_target_2qps

=== RUN TestEnvoyStack/2_authed_paths,_single_user,_target_4qps

=== RUN TestEnvoyStack/1_authed_paths,_dual_user,_target_4qps

=== RUN TestEnvoyStack/slow_path,_target_1qps

=== RUN TestEnvoyStack/unauthed,_target_0qps

--- PASS: TestEnvoyStack (50.02s)

--- PASS: TestEnvoyStack/single_authed_path,_target_2qps (10.00s)

--- PASS: TestEnvoyStack/2_authed_paths,_single_user,_target_4qps (10.00s)

--- PASS: TestEnvoyStack/1_authed_paths,_dual_user,_target_4qps (10.00s)

--- PASS: TestEnvoyStack/slow_path,_target_1qps (10.00s)

--- PASS: TestEnvoyStack/unauthed,_target_0qps (10.00s)

PASS

ok _/workspace/work/envoy_ratelimit_example/vegeta/loadtest 50.019s

Very satisfying. In only 50 seconds all 5 scenarios have been tested in a pretty robust way.

Final Thoughts

Envoy’s clearly well-engineered and truly excellent software, and I really enjoyed being able to look under the covers while trying to get the stack up and running the way I wanted.

For any use cases (especially higher volume ones) which require custom request processing, it’s well worth your consideration.