There is a time and place for repeatable infrastructure builds. I wouldn’t want anything to get to production without being terraformed/cloudformationed/etc.

However, there’s also a time and place for tinkering, experimenting, “hacking around”, and for that, “infrastructure as code” is often overkill.

Many times, the AWS console is a great place to start – pointing and clicking your way to victory. That gets annoying, quickly, though, if you’re doing a bunch of things that are similar but not identical; and it can also take a lot of clicks to discover information you need. The command line is an excellent middle ground.

- Quick discoverability; typing CLI commands can be a lot faster than traveling through several console screens and picking the right rows from dropdowns.

- Easy to copy/tweak/paste for light repeatability.

AWS’s own CLI is pretty solid, and they are working on a v2 version to improve usability. But there’s already a usability-focused AWS CLI tool available: awless.

The Goal: Experiment with a1 instances

AWS just announced an ARM-based computing platform: Graviton.

You can read about them in an AWS Blog Post or on the site of the always impressive James Hamilton.

I’ve personally been watching ARM in the datacenter for a long time. In the web hosting world it seemed very interesting – having more / cheaper / lower power CPUs could be a nice way to provide a better quality of service per customer in spite of ’noisy neighbors’, and the investment in ARM for mobile meant the effective compute power per watt was increasing rapidly as the desire for mobile power exploded. I also have used linux on ARM quite a bit with the Raspberry Pi. So, when they were announced, I was curious to play!

Because ARM uses a “reduced instruction set” vs the x86 “complex instruction set”, it’s difficult to compare performance directly, because what’s done in a single instruction can vary. I’d been looking for a quick way to generate a lot of HTTP load inside a private VPC subnet. That seemed like a good workload to compare – where the actual question of “how much work can you get done, how quickly” ends up being measurable. How many requests/second can be generated before the host gets unstable?

I chose caddy for the web server, because it’s a single simple binary and performs well, and vegeta for load generation for the same reasons. (Also, I have a history of vegetalove.) And because all architectures must be described with boxes and arrows:

Launch a server with awless

Ok, we’re tinkering, let’s get started. How do you create an instance? Luckily the self-documentation game is strong.

$ awless create instance -h

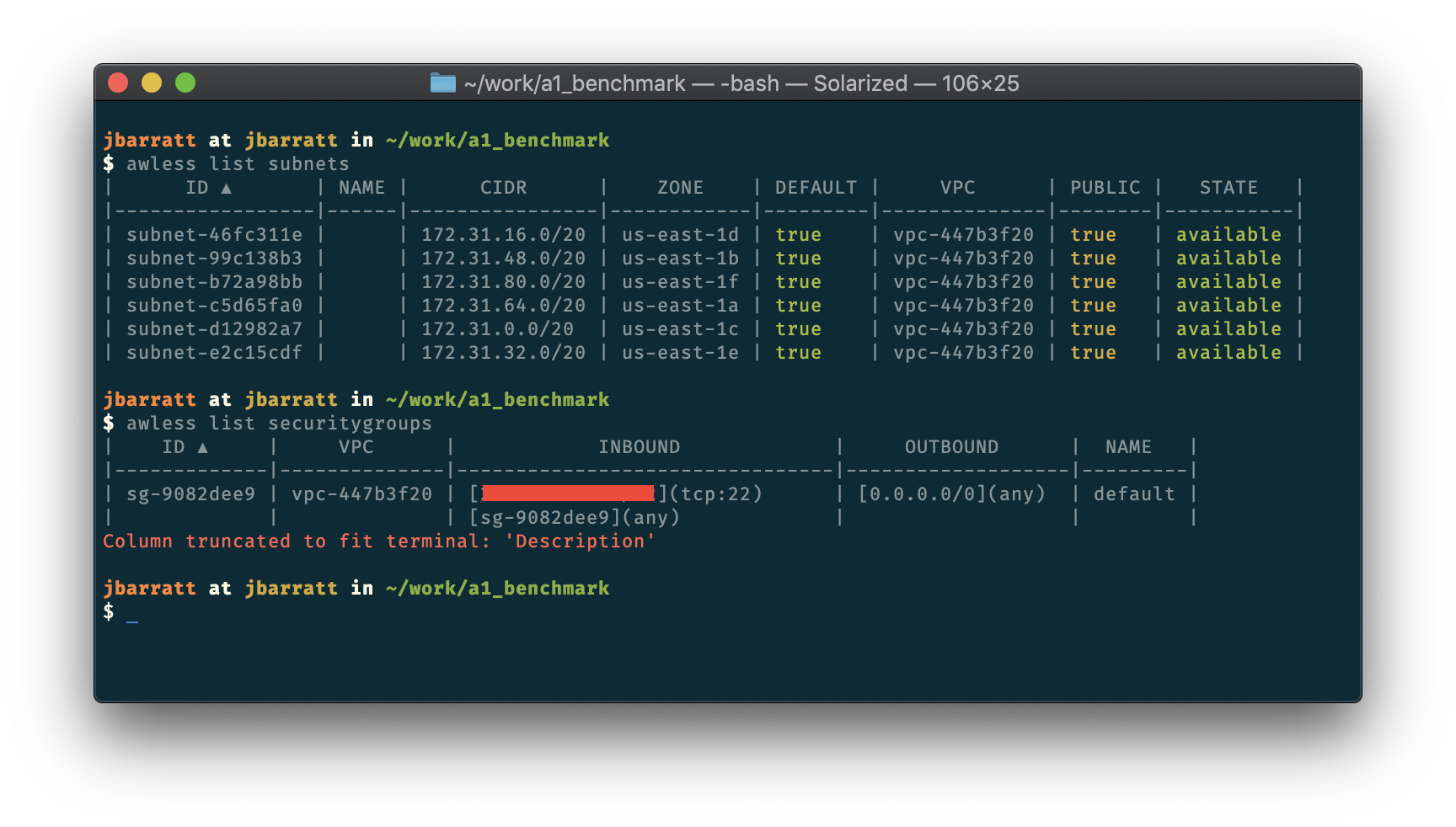

You can provide any params you want on the command line, and fill in other required ones interactively (with tab completion!) I was stuck needing to pick a good subnet and security group, though. This is easy:

From right in the terminal I can see which subnets are public and which aren’t. Running awless show <identifier>, like awless show subnet-46fc311e gives more information about things if needed. But I’m tinkering, and this is a scratch account, I just need a public subnet, and I’ve only got my default security group.

You may note the redacted box; that is my home IP, which is allowed to SSH into that security group. That’s a leftover from a previous tinkering session with awless; when I tried to ssh in, it couldn’t connect, and very helpfully suggested I may want to punch in a hole for myself with the following command. Notably, it figured out what my public facing IP was, and what the proper security group for the host I was connecting to was. It’s hard to imagine being more tinkering friendly than that.

$ awless update securitygroup id=sg-9082dee9 inbound=authorize protocol=tcp cidr=XX.YY.ZZ.QQ/32 portrange=22

I also needed to create a keypair for this account. That’s easy too:

$ awless create keypair name=mykey

The only place I had to go to the console was to find the proper AMI for an ARM host, but since that feature just launched, it’s probably ok that it’s not built in yet!

Now I can launch a host:

$ awless create instance type=a1.medium image=ami-0f8c82faeb08f15da subnet=subnet-46fc311e securitygroup=sg-9082dee9 keypair=mykey name=sledgehammer

Once it comes up, there’s a handy ssh capability, as well. As noted above, it’s smart enough to even recommend security groups, but it can also use jump boxes, guess the right username to use, and more.

$ awless ssh sledgehammer -i mykey

Get ready to load test

Sweet! So, for an ARM binary, I needed to request a custom build from caddy’s site, which ended up downloading locally, not on my fancy new host. Ok, now I need to scp… which means I need my IP address, and PEM file, things which awless had been handling for me. The IP address is easy to get with awless list instances, and it turns out, PEM files are stored by default in ~/.awless/keys/.

$ scp -i ~/.awless/keys/mykey.pem caddy ec2-user@54.167.228.17:

The other tools I need are a quick install or download/unpack away:

$ awless ssh sledgehammer -i mykey

$ sudo yum -y install tmux htop

$ wget https://github.com/tsenart/vegeta/releases/download/cli%2Fv12.1.0/vegeta-12.1.0-linux-arm64.tar.gz

$ tar -zxvf vegeta-12.1.0-linux-arm64.tar.gz

And, I wanted to let the machine work as hard as possible, with no chance of file descriptors becoming a bottleneck, so I added a few lines to /etc/security/limits.conf.

ec2-user soft nofile 900000

ec2-user hard nofile 1000000

tmux in 10 seconds

I’m using an app called tmux, another tool which is far more useful during experimenting and prototyping than for production.

If you’re not familiar, it’s a “screen multiplexer” – an app you run after you ssh to a machine, which provides both persistence (your commands keep running, even if you disconnect), and the ability to carve up your shell into multiple windows (virtual terminals you can flip between) and panes (vertical or horizontally split your terminal screen.)

It’s perfect here. No need to worry if my connection drops, and:

- One window to run

caddyas a webserver - One window to run

vegetaas a load generator - One window to run

htop, as it’s a very handy core-aware interface for quickly seeing if the host is really pegged, and if so, what’s doing it.

To do this, only basic tmux features are needed.

- To start using tmux, run

tmux. - To connect to a session already in progress, you attach to it. (

tmux a). - There is a special hotkey which you use to tell

tmuxyou’re giving it a command. By default, it’sControl-b. - Once inside a tmux, you can create a new “window” with the hotkey, then

c. (Default,Control-b, thenc) - You can navigate between windows a few ways, but I usually use

Control-b, p(previous) andControl-b, n(next), orControl-bfollowed by a number (1,2,3) for the window I want to go to.

Run the load test

I create 3 tmux windows, for htop, ./caddy, and vegeta.

Vegeta’s command line is also very composable and great for tweaking and playing with. I send in the URL (which caddy will serve), define the features of the ‘attack’, then dump out a report of the data.

$ echo "GET http://localhost:2015/README.md" | ./vegeta attack -duration=30s -workers=10 -rate=50 | tee results.bin | ./vegeta report

The README.md shipped with the vegeta tarball, so seemed like a reasonable file to use for the test. Use what you have.

I played around with the -workers and -rate setting by hand this time, though I have automated it before.

Finally, after some manual binary searching, the setting which ‘broke’ it was: -workers=10 -rate=2500.

Requests [total, rate] 13168, 1270.38

Duration [total, attack, wait] 17.211569325s, 10.36538365s, 6.846185675s

Latencies [mean, 50, 95, 99, max] 3.050666636s, 3.186014712s, 6.150334217s, 6.950259063s, 9.812459568s

Bytes In [total, mean] 251087424, 19068.00

Bytes Out [total, mean] 0, 0.00

Success [ratio] 100.00%

Status Codes [code:count] 200:13168

Error Set:

I asked for 2500 requests per second, and yet it was only able to generate 1270. You can also see that the latencies for the requests, usually in the 20-100ms range in earlier tests, are seconds. This machine is giving all it has to give.

So, I’m calling that the number for now: 1270 rps. Let’s see how the other team does.

Time to kill the server and stop paying … tiny fractions of a penny per minute for it! awless has our backs, of course.

$ awless delete instance ids=@sledgehammer

delete instance i-071ca8ea62f607dfe

Confirm (region: us-east-1)? [y/N] y

[info] OK delete instance

Comparison test with t3 instances

Looking at ec2instances.info the most comparable machine to the a1.medium is probably a t3.small.

- 2G of RAM, same as

a1.medium - Similar pricing ($0.0047/hr cheaper for the

t3) - 2VCPU for a “4h 48m burst” and a base performance of 40%

So, I know I need to do some of the same things again when I spin the new host up … and maybe I’ll want to test on some low end c’s and m’s as well. It’s not hard to make a small script that gets run at machine creation via userdata.

Pop this into setup.sh:

#!/bin/bash

yum -y install tmux htop

cd ~ec2-user

wget https://github.com/tsenart/vegeta/releases/download/cli%2Fv12.1.0/vegeta-12.1.0-linux-amd64.tar.gz

tar -zxvf vegeta-12.1.0-linux-amd64.tar.gz

wget https://caddyserver.com/download/linux/amd64?license=personal\&telemetry=on -O caddy.tar.gz

tar -zxvf caddy.tar.gz

cat >>/etc/security/limits.conf <<EOF

ec2-user soft nofile 900000

ec2-user hard nofile 1000000

EOF

I feel compelled to say that yes, downloading tarballs without checking their checksums, untarring them into a home directory, and running them from a shell – these are all bad things that one should never consider for production. But also, it’s wonderfully liberating to know that this machine will have a new home in /dev/null in literally minutes … if it gets me where I need to go faster, anything goes.

Bringing up a t3.small is now trivial:

$ awless create instance type=t3.small subnet=subnet-46fc311e securitygroup=sg-9082dee9 keypair=mykey name=t3small userdata=setup.sh

Within about 45 seconds I’m able to ssh in and begin the testing, no other tweaking required.

So, doing the exact same tests, what are the results?

[ec2-user@ip-172-31-19-157 ~]$ echo "GET http://localhost:2015/README.md" | ./vegeta attack -duration=30s -workers=20 -rate=5000 | tee resu

lts.bin | ./vegeta report

Requests [total, rate] 150000, 4988.30

Duration [total, attack, wait] 30.076498082s, 30.070365154s, 6.132928ms

Latencies [mean, 50, 95, 99, max] 27.77611ms, 22.313409ms, 69.037507ms, 109.292859ms, 230.308868ms

Bytes In [total, mean] 2860200000, 19068.00

Bytes Out [total, mean] 0, 0.00

Success [ratio] 100.00%

Status Codes [code:count] 200:150000

Error Set:

The t3.small hits the CPU redline, and starts to deliver fewer requests/sec than asked for, only at 5000 rps – and it still manages to deliver 4988 rps, or 3.9x more than the a1.medium

This means that even if it’s only running at 40% capacity after the burst window, it would still likely push out 1995 rps – still 1.5x more than the a1.

Interestingly, I tried the same test on a t3.micro (which just required a re-run of the previous command with different variables), and got almost identical results – though the credit cliff might be steeper.

Conclusions

I really can’t ‘conclude’ much, this test was tinkering-grade; not science or anything close to it. But I do suspect that right now in AWS, you can generate more brute force load testing requests/second/dollar on Intel than you can ARM. This being a heavily CPU-bound task, that’s in line with what even AWS says about them. It’s still an impressive first outing and I’ll be excited to see what other people do with them. There may be workloads with a different CPU / waiting for i/o ratio where they’d comparatively shine. They also do come with higher performance network than the t3s, which would be interesting to test. Perhaps when load testing across the network, the performance gap would shrink?

Hopefully you’ll share my conclusion that awless is a useful tool to have in the toolbox, especially for quickly creating and disposing of machines and other basic infrastructure. It fits very nicely in between “not worth terraforming yet” and “too annoying to use the console for.”