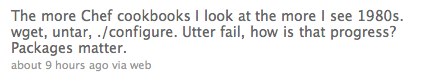

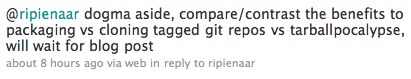

I woke up this morning to a discussion on twitter between two of my favorite internet people, Andrew Shafer and R.I. Pienaar.

Andrew I know from his previous job with Reductive (now Puppet Labs) and I love what he has to say. (I really liked his DevOps Cafe episode – in particular making me change my opinion about “commitments” in Agile contexts.)

R.I. is a force of nature – his blog is great, and full of years of hard-earned wisdom, and mcollective project is something I can’t wait to roll out.

The discussion centered around the question that I’ll paraphrase:

In the era of configuration management tools like Chef and Puppet, what value do packages provide? What are the pros and cons of packaging?

It was clear that both of them were feeling the pinch of expressing themselves in 140 characters. It’s a topic I’m pretty passionate about, after 15+ years fighting to keep systems under control, so I figured I’d write up my take on it.

Packages vs wget && tar

What are the pros and cons at the utility level?

(As dogma-free and objective as I can be, of course…)

The cost of building packages

Let’s start with the only downside I can think of to having to build packages – it’s an extra step, and takes some time.

Packaging your own code is easy – you solve it once, and then have something like Hudson or BuildBot take it from there. However, packaging upstream code that’s not in your distro is a pain in the butt. That’s a given.

Both of these get worse if (like me) you’re stuck running multiple distributions. Right now we have to build .rpm, .deb and Solaris packages.

Depending on what language you’re using, there might be some tools that help package things the right way. For Debian+Perl, for example, dh-make-perl is getting to the point of being awesome and very usable.

One way to get packages for upstream stuff that’s not very painful is with a tool like CheckInstall – you do the equivalent of a make install one time in a sandbox, and that gives you a package you can install at will and get all the benefits I’ll elaborate below.

No matter what, it’s an extra step.

@AshBerlin points out that, in the case that you’re managing some upstream software, that this is a cost you have to take on for every version they release, not just a 1 time cost.

There is no question that it’s ’easier’ to do a make install than to build a package (every time the software is updated) and get that installed.

So here’s why that’s worth putting up with.

The value of building packages

Redundant, Version-aware Repositories

What’s can go wrong with code that looks like this? (Arbitrary link I happened to have in my .bash_history)

$ wget http://yuilibrary.com/downloads/yuicompressor/yuicompressor-2.4.2.zip

- What happens when the version changes? You have to update your configuration. This can be a good or bad thing, but in some cases you really want

$latestto be installed, rather than the hard-coded version someone supplied the last time they edited the configuration manifest. - What happens when the yuilibrary folks change their (arbitrary) download URI’s?

- What happens if http://yuilibrary.com is down the next time you want to do a build?

- What if you want to be shipping

yuicompressor-2.4.1.zip? Is that still available for download?

When you want to install a package, the more reliable you can make the process, the better. Upgrading all the servers in a cluster? You want all the servers to be upgraded. Trying to bring a new server online? You want to be able to do that with a very low probability of anything going wrong. (The more you can trust your deploys, especially in the age of automated infrastructure, it saves you money to be able to bring servers up as “Just in Time” as possible.)

The “repo” model provided in at least the Red Hat and Debian packaging system handles all of these cases really, really well.

- You can provide a list of repositories that an attempt to install a package will try from until they find one working

- It’s a trivial sysadmin task to have several repos with the same content available. Each one doesn’t even have to be fancy and “HA”.

- It’s 100% predictable (and an implementation detail you don’t have to worry about) what will happen when you say you either want a specific version of a package, or the latest version.

Built-in “tripwire”-like functionality

Apt and Yum both keep checksums of all the files on the system installed by packages. So at any time you can ask “have any files supposed to be managed by packages been modified”?

- debsums

rpm -V -apkgchkon Solaris (/via @builddoctor)

This is a useful thing to know for security reasons, of course. However, it’s even more important for helping people adapt their behaviors.

In an environment that’s moving from “not configuration managed” to “configuration managed”, and the status quo has been “modify the files on production servers”, it’s great to be able to get a nagios alert that one of the servers is now out of configuration, check the sums, and find out exactly what file(s) and when were modified.

(If you couple that with a nice ’everyone logs in as their user and sudo’s when needed’ policy, you can find out exactly who and when, as well.)

The package manager knows how files got on your system

Knowing what files got spewed into your system from your average make install is pretty predictable, but certainly not always.

This is useful for 2 cases:

Troubleshooting, and knowing where to make changes when you find the problem

The server keeps throwing 500 errors. Why? Ah, an untrapped exception in /some/file/deep/on/the/system. Ok, I can fix that. Where do I need to go fix that? dpkg -S <filename> tells me the exact package responsible for that file.

$ dpkg -S /usr/bin/factor

coreutils: /usr/bin/factor

$ dpkg -S /usr/bin/facter

facter: /usr/bin/facter

That’s one area in particular where configuration management systems can add an extra layer of value. R.I. actually wrote a tool that helps you discover which puppet module is responsible for configuring a given resource on the server. (localconfig.yaml parser) So if the answer is, rather than “it’s something shipped with a package”, “it’s a config file that puppet wrote with your module called my_module”, you can easily find and fix it.

Uninstalling

I’ve had some concrete problems from this, where I did an upgrade, and cruft left over from the previous version interfered with the new versions. For dynamic languages which build up large library trees, this can be particularly nasty, since default search paths might end up including remnants of an old version.

When the package manager knows the location of every file, it can rip them out as happily as it put them in.

Dependencies are built in

At the level of configuration management, I really care about the application I’m configuring.

I want to run lighttpd. I tell the configuration manager to install it. I don’t want to have to do a research project to find all the supporting libraries required for it. Also, I really don’t want to track down the -dev versions of all of those libraries by hand.

This is especially important for upgrades – if an application starts using a new library after an upgrade (or depends on a newer version of a library when upgrading) that’s all handled (and expressible) at the package layer.

Discovery of available updates are built in

This is one of the most compelling reasons.

If you’ve got a system with 9 tarball’d packages,

- What versions are currently installed?

- What software has updates available?

It’s bad enough if you’re installing software you know about, but I assume we’re going to be using a distribution at some point. You also REALLY want to know about updates your distribution is providing, right? Especially when it’s things like critical kernel issues, openssl problems – anything that can be remotely triggered, at the very least.

Knowing what versions are available can be easily automated. You can use things like

to handle this, and even do things like automatically install security patches if you’d like.

Since you need to solve this ‘sysadmin problem’ at large anyway, why not leverage the tools and practices you build around this to learn about your own software, as well? It’s just as valuable to know that there’s a new build of apache2 available from the core Debian repo as it is to know that our_custom_app, which we expected to be at version 2.6 everywhere, is pinging because host25 is still running 2.5.

Cryptographic signatures are built in

Packages give you a way to trust that the bits you’re about to install are the ones you should be installing.

In this time of huge malware infestations, attempts to trojan even things like the linux kernel, and a large black market for “owned boxes”, you have every reason not to trust that the software you download isn’t compromised in some way.

Most places you can download tarballs also post checksums of what those files should be. There’s two problems with this:

- If you can’t trust the place the download is hosted, why would you trust the sum?

- That adds a lot of complexity to the automated installer.

You go from

- Download the package

- Decompress, configure, make

To

- Download the package

- Scrape for the latest checksums

- Verify the checksums

- THEN install the packages

Packages solve both problems.

- They distribute a public key asynchronously from the hosting of the packages. Unless you are owned already, you can verify that a package was signed by the person who holds the matching private key.

- Checking signatures is built in. Your package install will fail if something goes wrong.

Binary-identical code on every server

There are lots of things that can go wrong when you try and build a package from source.

- You may not have some development libraries you need. Great, now you’re stuck managing those explicitly in configuration management as well. This also means that

- Every server has to have the full stack of software needed to be able to build your software

- Compilation may fail, especially if the package was updated from the last time you tried to build it.

- Things that varied from build-to-build need to be accounted for when troubleshooting. “Huh,

redisonhost25keeps crashing. Do we need to rebuild it?”

In general, it’s very nice to be able to completely decouple the tasks of

- Creating a ‘build’ of your software and stack

- Deploying a ‘build’ of your software and stack

Environment Support

One reason we like packages and repos is that it lets us define a configuration as:

- A set of which packages

- A set of configurations of those packages

Then when we’re working in a topic or feature branch, we can create a repository just for that branch (this is also automated), and the repo configuration is the only thing that needs to be modified in the configuration management code.

Also, because you only need a subset of all the packages you need in a repo, this lets us “stack” them.

- Prefer my project repo (which only has my project-sensitive packages getting built into it, the stuff I’m modifying)

- Fall back to the production repo for anything else you need

The End

Packages may add some pain and complexity up front to the install process, but they add a tremendous amount of value to the “lifecycle management” of your applications. Most of the hell we go through as people running servers doesn’t happen the first month we set them up, it’s month 6, 18, and 24 that are the real problem. And those problems (“servers are graveyards of state”, etc) that make Configuration Management the right thing to do in the first place.

Use them. Love them.