Update: (03/2013) I’m not doing much Perl at the moment, but if I was, I’d probably be checking out Carton instead.

I’m really enjoying using Perl’s Dancer for building lightweight web applications. It’s heavily inspired by Ruby’s Sinatra framework, but clearly Perlish.

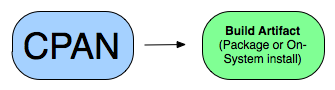

The only thing I’ve been bothered by so far is getting my applications from my development environment out to production. It’s pretty easy to actually do deployments in terms of actually getting your app up and handling web requests, but shipping the software to the remote system has always bothered me.

Update: I wanted to clarify that Dancer itself is very lightweight and has as close to zero dependencies as is reasonable to have.

However, the Dancer apps that I’ve been building tend to require a lot of pretty fresh CPAN goodness. (Task::Plack, Moose, DBIx::Class, AnyEvent, and more.) This is a problem if you’re trying to avoid using CPAN as root to just install system packages, which I like to avoid – it makes systems harder to define with something like Puppet, and can cause weird interaction problems between multiple applications running on the same machine when they use the same modules.

Dancer builds you a nice starter application container when you run dancer -a – it’s made to look like a Perl module, with a Makefile.PL and everything. This initially excited me, because I could just turn it into a debian package it with something like dh-make-perl. Here’s the problem – when you perl Makefile.PL && make dist none of your non-perl-module assets make the trip. I’m not really interested in deploying applications that don’t have templates, CSS, Javascript, or images.

From what I can tell in the docs and on IRC, most people solve this by just checking out their application from their version control system on the production box.

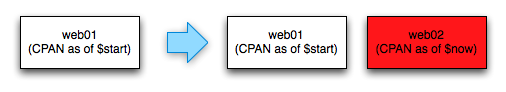

This is more or less this idea:

If you’re like me, and living life with hundreds or thousands of servers, that approach doesn’t really work. It also doesn’t solve the first problem above of how to handle all the dependencies (or dependency clashes on a single machine.)

If you’re running lots of servers, you’ll end up with this problem. You install your first app on a single box or two, and it’s running along fine. Then the people come, and you need more horsepower. Time to build a new box.

Oops! DBIx::Class isn’t passing tests right now. I guess we can’t deploy a new server. Or, more subtly, everything installs, but when you add your app to the load balancer, something is “wacky” one 1/2 of the web requests. Pleh.

You really don’t want to be in that trap if you’re trying to auto-scale your app on, say, EC2.

Ok, so we don’t want to install from CPAN on the fly.

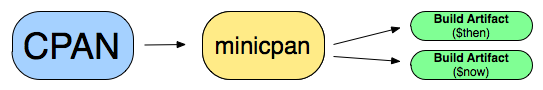

I really like brian d foy, and he’s got a strategy to handle this problem: run your own CPAN!

This is actually a pretty good idea, and in some environments, I’d be using it right now.

That turns the model to this:

We have our own minicpan to use to buffer the volatility of the CPAN. Upgrades can happen to minicpan when we want and need them to. If the minicpan didn’t change, we can install our application on as many servers as we want, and trust they’ll be getting the same code.

There’s still a big problem with this: what if you have multiple apps that have different dependencies? You can’t use CPAN’s “new hotness” for one simple app that could really use from it, without worrying about if all your other applications will be able to work with all that new code. So we’ve given ourselves the ability to add a ‘buffer’ between our usage and CPAN’s potential volatility, but we haven’t bought much independence for our applications.

Brian’s started working on extending minicpan to handle multiple minicpan’s.

However, there is another approach, which brings some other nice features as well.

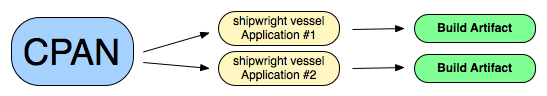

Enter Shipwright.

Shipwright lets you keep a local, version-controlled copy of all the source (from CPAN or otherwise) that your application needs. It keeps the information about where all that source “came from”, be it CPAN or a local file, so you can keep it as up to date as you want to, and when you want to. It nicely decouples the “application building and packaging” problem (“make me a new package”) from the “application maintenance” problem (“update some components.”)

So now we’ve got a version controlled “CPAN Cache” per application we’re managing.

The other things I really like about Shipwright are:

- It doesn’t just handle the CPAN problem – it also makes your code into a little self-contained unit which can be dropped into any directory on the target system.

- You can tweak any module’s “build process”. (As I take advantage of below.) If the CPAN installer doesn’t work the way you want or need, you can do some pre/post-install hacking. Again – in a nice, version controlled and repeatable way.

- You can ship

autoconfstyle applications along with it. Want to also deploy a patched version ofnginx, or aredisserver? You can do that here. (I wouldn’t, but you can.)

Essentially, all I’m saying is “use shipwright” – but there are a few tricks to make it work for Dancer applications.

MANIFEST

First, you’ll need to make sure all the files you care about in your Dancer app are going to be included at all. This means getting them in the MANIFEST file. I just did a simple find . -type f > MANIFEST and cleaned out the entries I didn’t need or already had. If you’re doing this a lot, or modifying the file contents of your applications a lot, I’m sure there’s a more elegant approach.

shipwright build file

One of the nice things about shipwright is that it allows you to tune up a build script for everything you’re installing.

Even though the Dancer packages now contain all your files, they still don’t know where to get installed.

Normally the scripts/MyApp/build contents look like this:

install: %%MAKE%% install

If we add a simple extra step, that gives us a copy of all the module’s assets rooted off our package’s ‘/www’ path.

install: %%MAKE%% install ; cp -av . %%INSTALL_BASE%%/www

Walkthrough

First, you’ll need to install Shipwright. I am in love with the mighty combination of local::lib and cpanm, so I’d recommend starting there.

Build your Dancer app

Once you’ve fixed the MANIFEST file as described above, you need to build a distribution of your Dancer app.

$ cd ../MyApp

$ perl Makefile.PL

$ make dist

Prepare the ‘vessel’

I’m going to be doing all the work in a directory called ~/home/work/shipwright.

I’m also using the git shipwright backend here – it works with svn, plain filesystem, and other options as well.

# you might need to mkdir -p "$HOME/work/shipwright/" first.

$ export APPNAME="MyApp"

$ export SHIPWRIGHT_SHIPYARD="git:file:///$HOME/work/shipwright/$APPNAME-vessel.git"

$ shipwright create

Ok, now you’ve got the vessel. It’s time to load it full of CPAN’y goodness. Since this is a tutorial for Dancer, I’ll include some of the basics I like to have when deploying Dancer apps.

Fill the vessel with software

I’m using --no-follow here because I had some errors trying to follow dependencies on my internal applications that I also install via distribution file. If you’re only loading CPAN modules from your Dancer app, you can take this off.

$ shipwright import cpan:Template cpan:Dancer cpan:YAML::XS cpan:Task::Plack

# put the full path, and right version number of, the file here

$ shipwright import file:~/work/$APPNAME/$APPNAME-0.004.tar.gz --no-follow

# REPEAT importing for any of your other in-house modules/code

$ cd ~/work/shipwright

$ git clone $APPNAME-vessel.git

$ cd $APPNAME-vessel

$ vi scripts/$APPNAME/build

# change the install line from:

# install: %%MAKE%% install

# to

# install: %%MAKE%% install ; cp -av . %%INSTALL_BASE%%/www

$ git add scripts/$APPNAME/build

$ git commit -m "tweaked build script for $APPNAME"

$ git push origin master

Build the vessel

Cool. Now we’ve got a self-contained, versioned repository. Time to build it.

$ ./bin/shipwright-builder --install-base ~/work/shipwright/$APPNAME --force

The --force is because some modules don’t pass tests. Shipwright does have a ways to go with dependency management (or I’m doing something wrong) – if I’ve install a module into the ‘vessel’, sometimes other modules that depend on it can’t use it at build/test time.

Now you’ve got a directory (~/work/shipwright/$APPNAME) which can be deployed repeatably on your servers. You can wrap it up in a Debian or Red Hat package if you’d like, tar it, rsync it, BitTorrent it – up to you.

Maintaining the Vessel

When you build a new version of your Dancer app, all you have to do is update the vessel, then build.

$ shipwright relocate $APPNAME file:~/....new.tar.gz

$ shipwright update $APPNAME

$ cd $APPNAME-vessel

$ git pull

$ rm -rf ~/work/shipwright/$APPNAME && ./bin/shipwright-builder --install-base ~/work/shipwright/$APPNAME --force

Using the Vessel

Shipwright has some nice features to set up all the environment variables needed so you can use your app. All you have to do is source the appropriate script, like so:

# set up your environment so the '$APPNAME' libraries and binaries are in your path

$ . /opt/yourstuff/$APPNAME/tools/shipwright-source-bash /opt/yourstuff/$APPNAME/

What’s cool is you can do the same thing from SYSV-style init scripts. Let’s say you’re launching this as a fastcgi application.

Your startup script can look like this example. The magic line is source $APP_BASE... which uses the shipwright shell config to set the variables used by the rest of the script.

#!/bin/bash

NAME=$APPNAME

APP_BASE="/opt/mt/$NAME"

source $APP_BASE/tools/shipwright-source-bash $APP_BASE

APP_BIN="$APP_BASE/bin"

APP_WWW="$APP_BASE/www"

APP_PSGI="$APP_WWW/app.psgi"

FCGI_LISTEN=127.0.0.1:55900

DAEMON="$APP_BIN/plackup"

# Defaults

#RUN="no"

OPTIONS="-s FCGI --listen $FCGI_LISTEN -E production --app $APP_PSGI"

PIDFILE="$NAME.pid"

[ -f /lib/lsb/init-functions ] && . /lib/lsb/init-functions

start()

{

log_daemon_msg "Starting plack server" "$NAME"

start-stop-daemon -b -m --start --quiet --pidfile "$PIDFILE" --exec $DAEMON -- $OPTIONS

if [ $? != 0 ]; then

log_end_msg 1

exit 1

else

log_end_msg 0

fi

}

signal()

{

if [ "$1" = "stop" ]; then

SIGNAL="TERM"

log_daemon_msg "Stopping plack server" "$NAME"

else

if [ "$1" = "reload" ]; then

SIGNAL="HUP"

log_daemon_msg "Reloading plack server" "$NAME"

else

echo "ERR: wrong parameter given to signal()"

exit 1

fi

fi

if [ -f "$PIDFILE" ]; then

start-stop-daemon --stop --signal $SIGNAL --quiet --pidfile "$PIDFILE"

if [ $? = 0 ]; then

log_end_msg 0

else

SIGNAL="KILL"

start-stop-daemon --stop --signal $SIGNAL --quiet --pidfile "$PIDFILE"

if [ $? != 0 ]; then

log_end_msg 1

[ $2 != 0 ] || exit 0

else

rm "$PIDFILE"

log_end_msg 0

fi

fi

if [ "$SIGNAL" = "KILL" ]; then

rm -f "$PIDFILE"

fi

else

log_end_msg 0

fi

}

case "$1" in

start)

start

;;

force-start)

start

;;

stop)

signal stop 0

;;

force-stop)

signal stop 0

;;

reload)

signal reload 0

;;

force-reload|restart)

signal stop 1

sleep 2

start

;;

*)

echo "Usage: /etc/init.d/$NAME {start|force-start|stop|force-stop|reload|restart|force-reload}"

exit 1

;;

esac

exit 0

Conclusion

Dancer is great. Shipwright is great. CPAN is great, but I want a buffer from all that awesomeness.